The Case for Redistricting Advocates to Use Geospatial Software

Prior to mainstream use of geospatial software in redistricting, organizations participating in the redistricting process found themselves locked out of the system or even drawing maps by hand. Government organizations trying to open the process to the public were subject to expensive software contracts with difficult-to-use software. Yet, redistricting is a fundamental area of democracy where sophisticated spatial analysis is vital. Today, many organizations still find their options limited to expensive software that fails to involve the public in their application. These organizations, frequently non-profit or government entities, tend to have limited budgets. For us to have an accurately represented society, affordable and accessible software that meets these organizations’ needs is essential.

The Challenges of Redistricting

The challenges of redistricting concern both the process and data behind it. The process for redistricting varies by state and is often difficult for the public to understand. Another factor that makes it difficult for public involvement is the lack of accessibility of the data that informs redistricting. Typically, it is derived from census data. This data is incredibly cumbersome and difficult for the average person to decipher, let alone use it to draw district lines. Furthermore, when people lack access to this data they cannot make the case that a map may not be truly representative. Finally, elected officials, who are partisan figureheads, are typically involved in the process. Even with a nonpartisan commission, the public is still left out of the process.

Involving the Public in Redistricting

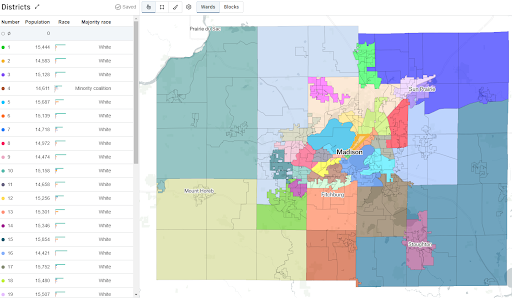

Despite these challenges, government and advocacy organizations alike are striving to spark change by involving the public in redistricting. This is what drove Dane County, Wisconsin to choose DistrictBuilder. DistrictBuilder is an open-source redistricting tool that was built with the purpose of involving the public in the redistricting process. A key feature that allows for this is DistrictBuilder’s organization page. Organization pages give groups of concerned citizens, nonprofits, and government entities the ability to create their own online mapping community. Users can join the organization and begin drawing their own maps. All of the maps in that community are grouped under one page so the public can view the different options that are showcased. This easily allows for the public mapping process Dane County was pursuing.

The Public Mapping Process in Action

Dane County’s Redistricting Commission brought three maps, resulting from input from DistrictBuilder maps, to the clerk’s office for review and final adjustments. The Commission was required to create maps with districts that were equal in population, minimized crossing in municipal boundaries or wards, provided effective representation of minorities, considered natural geography, and maintained communities of interest. After the Redistricting Commission submitted its maps, the Board Chair mentioned that he hoped their work could serve as a model of a fair, public-driven map-drawing process.

Dane County Approves Final Supervisory District Map

For Dane County, this was the first time elected officials were kept out of the redistricting process. The approved map met the criteria the Commission set out. It involved the public and prevented elected officials from influencing the final districts. It also kept some of the rural areas to the far east and west more compact while splitting up the fewest number of wards. Finally, the map also had five districts where the population of minority constituents was 40% or greater.

DistrictBuilder allowed Dane County to easily update its process and create maps with public input. Our hope is that all governments going forward can involve the public in their redistricting process to bring transparency to a process that has historically been opaque. DistrictBuilder can play a part in that change.